Chapter 05

Research

Research

The first step is to dig into the problem and find those patterns and commonalities you can use to push the project forward and get buy-in from every stakeholder. There are two ways to come at this: user research (both internal and external) and content analysis.

User Research

Most user research in the last decade has focused on external users of a website. Your “customers.” For a university, these might be alumni, students, parents of students, faculty, etc.

However, in an archipelago, it can be useful to bring those same tactics to bear on your internal customers. These will be your various schools, departments, faculty (again), deans, and more.

Why user research? It helps you prioritize your target audience. Otherwise, you just try and do everything for everybody.

For external users, that can manifest as dumping every piece of information out there “just in case” with no sense of how it should be prioritized. Or worse: everyone fighting over how it should be prioritized. Users have to lean on a search function that probably doesn’t work very well. No one can find anything. No one is happy.

For site editors, it can manifest as giving everyone HTML access and hoping for the best. This leads to an unmaintainable mess with zero chance of standardization or content re-use.

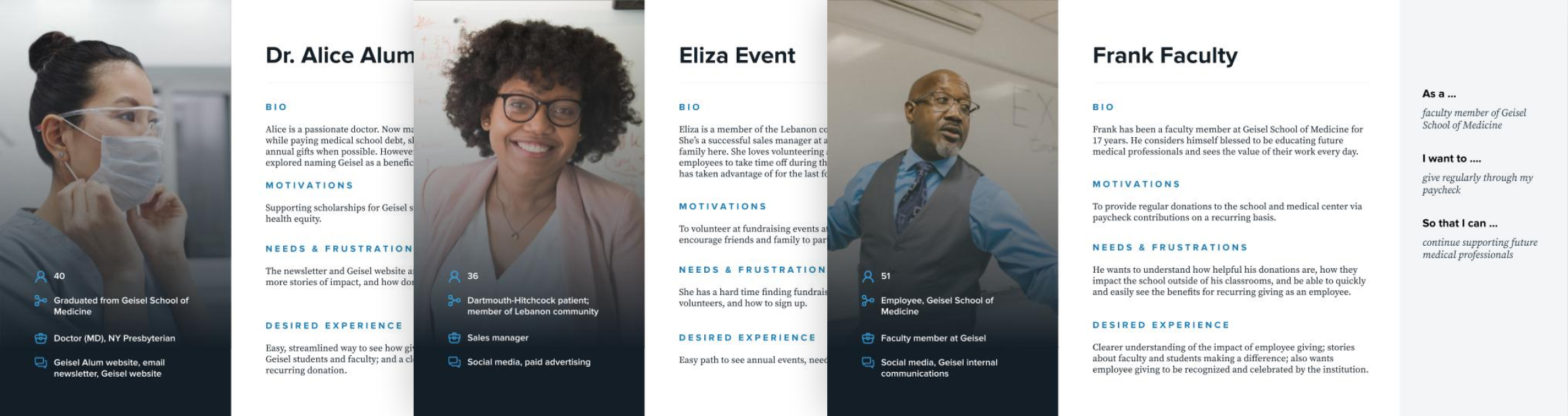

User personas are typically used to focus on solutions for customers, but you can use them effectively for your internal user base. For example, the State of Georgia created very detailed user personas for their agency users, dividing them into the six most common personalities and laying out a variety of information that defines them. Each persona included their motivations, frustrations, common software, goals, and much more. They also defined common “verticals” for their agencies, such as Elected Officials and Law Enforcement.

Just like with your customers, having personas allows you to take a very broad base of people and narrow it down to the groups you need to focus on. It also allows you to spot commonalities. So develop some personas.

Now, as you talk to users about their use cases and pain points, you can make sure you get a good representation for each persona. You are more likely to include the full range of subsidiary use cases.

As you interview them, you will hear a lot of complaining and cataloging of needs. You need to dig for the “why.” What motivates their use cases? What are they actually trying to accomplish when they hit roadblocks? Often, the obvious issue isn’t the actual issue.

Here is an example.

On one archipelago project, everyone wanted us to address design issues. They complained about not having access to something, or they needed to move a photo here, or make it bigger there, or control the output for a callto-action. Many of these needs contradicted one another. There was no consensus other than everyone wanting some variation of “just give me HTML access.”

We asked two questions to get to the root of the problem and try to find the magical intersection.

- Why did they need this specific design control?

- What was the driver or business goal behind it?

Internal politics or directives from those in authority might be common reasons for these requirements, but that was not the case here. As it turned out, there were no specific design goals. They also were not trying to fulfill specific requests. They didn’t actually need to place a specific photo in a specific place.

The main driver: they just wanted to “break up the wall of text.” They thought their pages were “boring” and looked “dated.” The more we researched, the more this specific complaint popped up.

With the problem identified, we could now design a solution and validate it with acceptance testing.

When doing user research, don’t take what people say at face value. This adage is true: you need to ask why five times before getting to the heart of a problem. It’s easy to just do what you’re told, but you won’t be serving your users very well.

When you understand users’ motivations, you can design for them, and if you can design for them, you have a way better chance of keeping them happy.

There is no shortcut to this—just a lot of conversations.

By taking the user research tactics normally used for end-users and applying them to internal users, you get a better picture of your stakeholders at the subsidiary groups. By constantly focusing on the “why” of their needs, you can start to put together commonalities and gain real insights into problems. And if you can solve some real problems, you’ll be able to dangle a very tasty carrot in front of these users.

Content Analysis

To do proper analysis, you need to do an inventory and audit. At the scale of archipelagos, this can be difficult. You might not even know all of the sites that exist under your domain. And once it’s all gathered, you need to be able to sift through it to find the relevant content for a particular conversation. Out of the millions of pages of content, what items are relevant to the three stakeholders I am talking to today?

This is more art than science.

Here is what you must do:

- Get an aggregated inventory of all content from across your sites

- Divide in different ways and research the outliers

Use a tool like Screaming Frog to crawl your sites and generate the inventory of content. At every URL. Your initial instinct may be to limit what you crawl because there is an enormous amount of data at this scale.

Kill that instinct. Crawl everything.

Large data sets can be filtered, sliced, and organized, but you can’t do any of this with data that you don’t have. Every time you have to go back to the well to crawl more content causes additional delays. Do it once. Get it over with. If you have a large amount of data, don’t expect to use Google Sheets to sort through the data. Just get Excel.

FIND THE EXTREMES

Armed with this large amount of data, start looking for the extremes. Extremes of what? Anything. Outliers can provide a lot of insight into the various teams within your archipelago and the content they create.

Look for edges around these items:

- Page size (largest and smallest)

- Google Analytics visits (what is nobody looking at? Why?)

- H1/Title size (can point to poor editorial practices and difficult migrations)

- Text:HTML ratio

- The number of embeds (images, tables, social media, etc.)

But you might also come up with other custom properties to measure.

Let’s look at page size as an example. Seeing what lives at both the highs and lows of this measure can be really interesting. Some of the reasons will be obvious, like huge tables. But sometimes you find something interesting.

In one archipelago project, we found the largest page on the entire network of sites. Someone had base-64 encoded an image and embedded it into the HTML using the WYSIWYG. This told us a lot of things, but mainly that end-users of the CMS can be very crafty in getting around limitations. You can use this information when planning out editorial tools.

Looking at the smallest page sizes can also yield insight. In one case, we unearthed some document management problems by looking at this metric. A large number of pages were nothing but an uploaded document with no context or metadata.

Most of the time, you won’t find anything of note. This is good. It lets you move on to the next thing. You don’t want the extremes to be a nightmare.

AGGREGATE AND DIVIDE

In an archipelago, some information will be important in aggregate, some will be more important based on the islands, and sometimes both will be important in different ways. You shouldn’t ignore the importance of either and always look at the data through both lenses.

Here is an example. On one project, we noticed that, across all sites, there were far more PDF and DOC files on the sites than there were HTML pages.

In aggregate, this told us that an enormous amount of information was locked away in these documents that might be worth getting out.

However, when we zoomed in, we discovered that the highest PDF to HTML content ratios were limited to a smaller number of sites. A lot of sites did well and limited PDF abuse. And even in sites with a lot of PDFs, there were outliers.

If a site has to offer a lot of printable forms (like a Department of Revenue, for example), then having a lot of PDFs makes sense. But some sites had weekly meeting minutes posted that went back ten years. This highlights potential problems around governance and best practices. How long should these documents be kept? Are they really that important? Are there better ways to manage them?

By looking at the content being created from different viewpoints, you’ll be able to gain insights and identify systemic issues for the organization at large and the individual islands.